The urbanization of water poverty

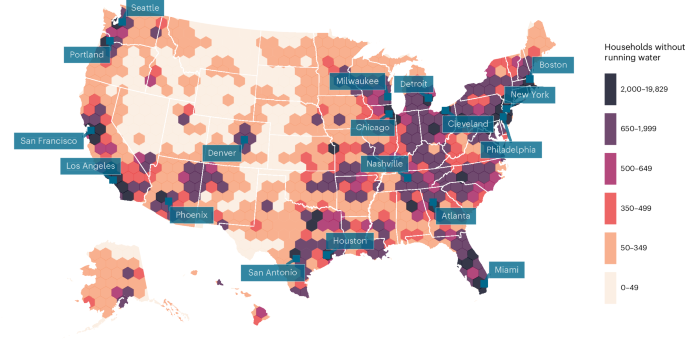

Over the twentieth century, the story of water access inequality in the United States has morphed from a predominantly rural to a majority urban problemâa process we call the urbanization of water poverty. Nationwide, the United States has made great strides in improving water and sewerage access since the 1970s, when 3.5 million households lacked indoor running water and a flush toilet. Still, in 2021, more than half a million US households (1,100,000 people) lacked running water in their homes, a population equivalent to Austin, Texas (the tenth-largest city in the United States). Today, more than seven in ten US households without running water are in cities (71.7%), including major urban areas along the West Coast, Eastern seaboard and Sunbelt regions (Fig. 1). Clearly, while rural areas continue to suffer from exclusion and racial disparities in access to municipal drinking water systems30,31, the nature and character of plumbing poverty in the United States is decidedly urban.

Cities with notable concentrations are listed by name. Source data: US Census Bureau.

Source data

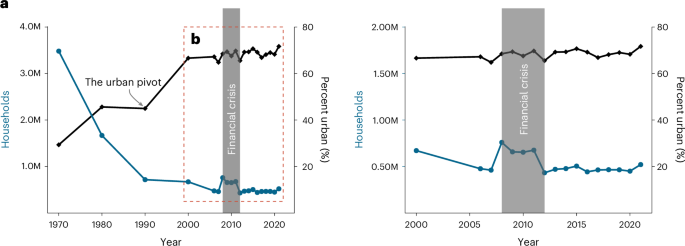

When did the urbanization of plumbing poverty gain traction? Across the United States, we identified a clear shift in the demographic composition of plumbing povertyâmeasured as households without access to running water (Methods)âfrom majority rural to majority urban beginning in 1990, a shift we call the âurban pivotâ (Fig. 2a). During the 1970s and 1980s, the percentage of households without running water started to rise in urban areas, but the process accelerated >50% in the decades after the pivot (Fig. 2a).

a,b, Dual-axis line plots show (1) an overall decline in the total number of US households without running water (blue) and (2) an increase in the urban share of all US households (black) without running water relative to the nationwide total during 1970â2021 (a) and 2000â2021 (b). The âurban pivotâ marks a shift in the share of plumbing poverty to >50% in urban areas. The grey box marks the immediate period of housing instability and foreclosures following the 2008 financial crisis. Source data: US Census Bureau.

Source data

Plumbing poverty rapidly urbanized between 1990 and 2000 as the urban share jumped from 45% to 66.6% in just ten years (Fig. 2a). During this period, plumbing poverty increased by 124,000 households in urban areas (323,000 to 447,000, a 38.4% increase) and decreased by 171,000 households in rural areas (395,000 to 224,000, a 43.3% decrease). Plumbing povertyâs urban pivot coincided with a nationwide expansion of home mortgage lendingâfueled by cheap loans and financialized assetsâand a concentration of housing wealth3,4,6,32. In 1990, 59,031,378 US residents (64.2%) owned their own home. By 2000, the number of US homeowners increased by roughly 10 million people to 69,815,753 (66.2%), an increase of 18.3% in ten years. As US cities grew vis-Ã -vis ownership and speculation in the housing market, affordable housing optionsâin terms of renting or owningâfor low-income residents began to evaporate3,4,6,32.

A closer examination of the 2000â2021 period revealed that swings in plumbing poverty corresponded with major shocks in housing affordability, particularly for low-income, asset-limited households (Fig. 2b). The global financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermathâa period known as the âGreat Recessionâ in the United Statesâwas a major catalyst for economic transformation and structural change in the US housing sector, with implications for safe and secure water access. In the years directly following the crisis, US cities struggled with high foreclosure rates, vacant properties and repossessed homes1,4,8. By 2012, more restrictive mortgages and a post-crisis rental demand drew new actors and large-scale investors to the single-family rental property market, including private equity firms and corporate landlords3,4,5,8,32. In many US cities, the housing market rebounded and grew, leading to steep rises in median rent and home sales that âsqueezedâ low-income urban dwellers, especially people of color3,4,33.

Indeed, our analysis shows the housing financial crisis pushed more households into plumbing poverty. Results indicate a two-pronged uptick in the number of US households without running water, first evident in 2008 and then again, at a slower rate, starting in 2016 (Fig. 2b). Following the 2008 crash, the number of US households without running water immediately shot upwards (the first uptick) from 461,000 in 2007 to 760,000 in 2008, an increase of 300,000 households (65%) (Fig. 2b). As the country emerged from the crash and households adapted to a newly restructured housing landscape, the total stabilized at approximately 475,000 households without running water until the middle of the decade. A second, steadier uptick began in 2016 and continued through the COVID-19 pandemic: from 465,000 households without running water in 2019 to 534,000 households in 2022, an increase of 15%.

In sum, despite an overall improvement in household water access at the national level since the 1970s, our results identify two pernicious and persistent trends: first, a concentration of plumbing poverty in US cities; and second, a clear relationship between significant âshocksâ in the political economy of housing and increased rates of plumbing poverty.

The racialized nature of water access trends

In a closer examination of pre- and post-crisis trends in the 50 largest US citiesâhome to roughly half (47%) of all US households without running waterâwe discovered that water access worsened for people of color between 2000 and 2021, even in cities with healthy economies and population growth.

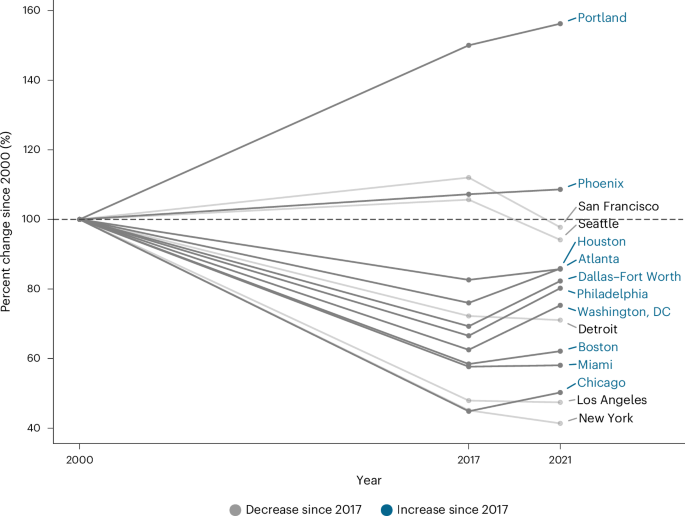

First, the good news: across the country, levels of plumbing poverty declined or remained steady in many US cities over the last 20 years. We found 83,200 fewer households without running water across the largest 15 US cities in the 2017â2021 period as compared to 2000, a 37.5% decrease (Table 1). Despite having some of the largest numbers of households without running water, New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago recorded the largest absolute drops and Miami; Boston; Detroit and Washington, DC, also registered significant declines (Table 1). In New York City, for example, there were 35,000 fewer households without running water in 2017â2021 compared to 2000, a 58.6% decline. Still, New York City remained home to the most households without running water (24,700) in 2021, followed by Los Angeles (17,400) and San Francisco (12,900); combined, an estimated 127,000 people in these three cities live without running water. Elsewhere, rates of plumbing poverty stagnated: meaning the numbers of households without running water remained virtually unchanged. Little to no change occurred in San Francisco and Seattle, which averaged 14,000 and 5,000 households (respectively) without running water in the most recent period (Table 1).

However, a second finding confirms a worsening scenario for households of color in US cities since 2000. Despite overall improvements across US cities, our analysis found that household water access âgainsâ are racially skewed towards White improvementâin some cities, at several orders of magnitude. People of color represent the majority of individuals without access to running water in 12 of the 15 largest US cities, including Los Angeles (82%), Miami (79%), San Francisco (74%) and Houston (71%) in the 2017â2021 period (Table 1). Our analysis indicates substantial overrepresentations relative to city-specific racial distributions, expressed as the âracial disparity rateâ in Table 1. For example, in 2021, people of color comprised 54% of the population in New York City compared with 68% of its population without access to running water, an overrepresentation of 14% (Table 1). Racial disparity rates were the highest in Philadelphia (26%), followed by Phoenix (23%), Detroit (22%), Boston (15%), New York City (14%), Portland (12%), San Francisco (12%) and Chicago (12%). Taken together, our results suggest that improvements for White urban households came at the expense of urban households of color, most evidently in cities with otherwise progressive policies and healthy economies.

Third, we find that plumbing poverty has selectively increased since the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the fact that many US cities (and states) adopted temporary but expansive COVID-era welfare policies such as water and energy shut-off moratoriums (which prevented utility service disconnections) and household support programs such as unemployment benefits, childcare tax credits and student loan forbearance24. Between the 2013â2017 and 2017â2021 periods, the numbers of households without running water increased in 12 of the 15 largest US cities (Fig. 3 and Table 1), with the largest numerical increases in DallasâFt. Worth; Philadelphia; Washington, DC; Houston and Chicago (ââ¥â1,000 households per city; Table 1). We calculated the percentage change for each city (Fig. 3) between 2017 and 2021 and found increases in Portland, Oregon; Phoenix; Houston; Atlanta; DallasâFt. Worth; Philadelphia; Washington, DC; Boston; Miami and Chicagoâcities that, as we explain below, experienced a dramatic rise in housing and living costs during and after the pandemic. In sum, our analysis indicates that the most recent phase in the urbanization of water povertyâcharacterized by a reproductive squeeze in affordable housing and a selective erosion of conditions for low-income households of colorâshows no signs of slackening or reversal.

Indicates directionality and percentage change in plumbing poverty among the 15 US cities with the largest absolute number of households without access to running water between 2000 and 2021. Ten cities (in blue) experienced an increase in the percentage change from 2017â2021, meaning their access levels have deteriorated relative to other cities. All cities recorded statistically significant changes between 2000 and 2017â2021 (except Phoenix, San Francisco and Seattle). Source data: US Census Bureau.

Source data

The reproductive squeeze

Portland provides a bellwether case to understand the core mechanism at work in these trends: the reproductive squeeze. In this concept, the capacities of people to reproduce themselves on a daily and societal basisâdefined as âsocial reproductionââare âsqueezedâ in advanced capitalist societies as capital restructuring and austerity policies transform or roll back support infrastructures, in effect downloading social responsibilities onto individuals in uneven ways25,26,27,28,29. Here we argue that a confluence of politicalâeconomic trends, driven by post-crisis changes in the housing market, have squeezed low-income and racialized urban households into more precarious but less expensive living arrangements. Put differently, the cost-of-living crisis and lack of safe, affordable housing in US cities have forced more households into homes without running water, resulting in deteriorating levels of household water access even within the United Statesâ most prominent cities.

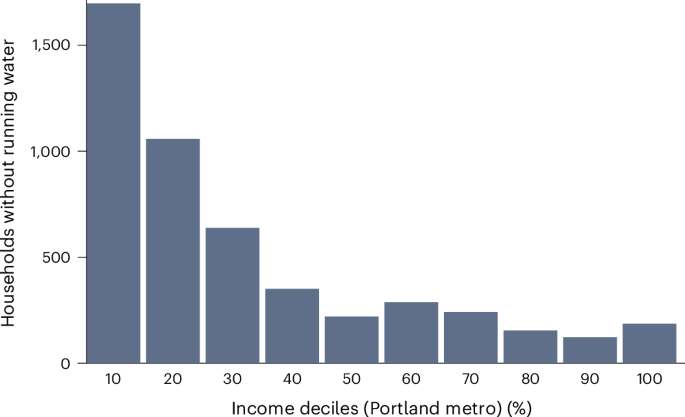

As Fig. 3 indicates, Portland ranked worst among 15 US cities for the percentage change in plumbing poverty since 2000 (a nearly 60% increase), despite its reputation as a model of sustainable urbanism with progressive urban planning34. From 2000 to 2021, we found that plumbing poverty in Portland increased by 1,800 households (56.3%) during a period of rapid population and economic growth and significant wealth gains in the homeownership market. Several structural changes particularly squeezed low-income Portlanders. Whereas median household income in Portland increased by US$16,700 (or 23%) over the last decade (US$72,600 in 2012 and US$89,300 in 2022), the median home sales price increased by US$325,100 or 140% (US$231,900 in 2012 and US$557,000 in 2022) during that same period35,36. Portland renters now face a rental housing landscape that has far outpaced household earnings: median rent increased from US$900 to US$1,600 between 2012 and 2022, a US$700 increase (77.8%)37. Moreover, as a local journalist reported, professional and corporate investors have made significant inroads as owners in the Portland rental housing market, taking advantage of population growth and low vacancy rates to drive up rents well beyond the means of low-income households38 (also refs. 4,5). Many Portlanders have left the city; since 2020, Multnomah County (which includes nearly all of Portland) has experienced the first population decline in 40 years. For the Portlanders who have remained, they must find new ways to pay higher living costsâincluding, we suggest, moving into less expensive housing without running water.

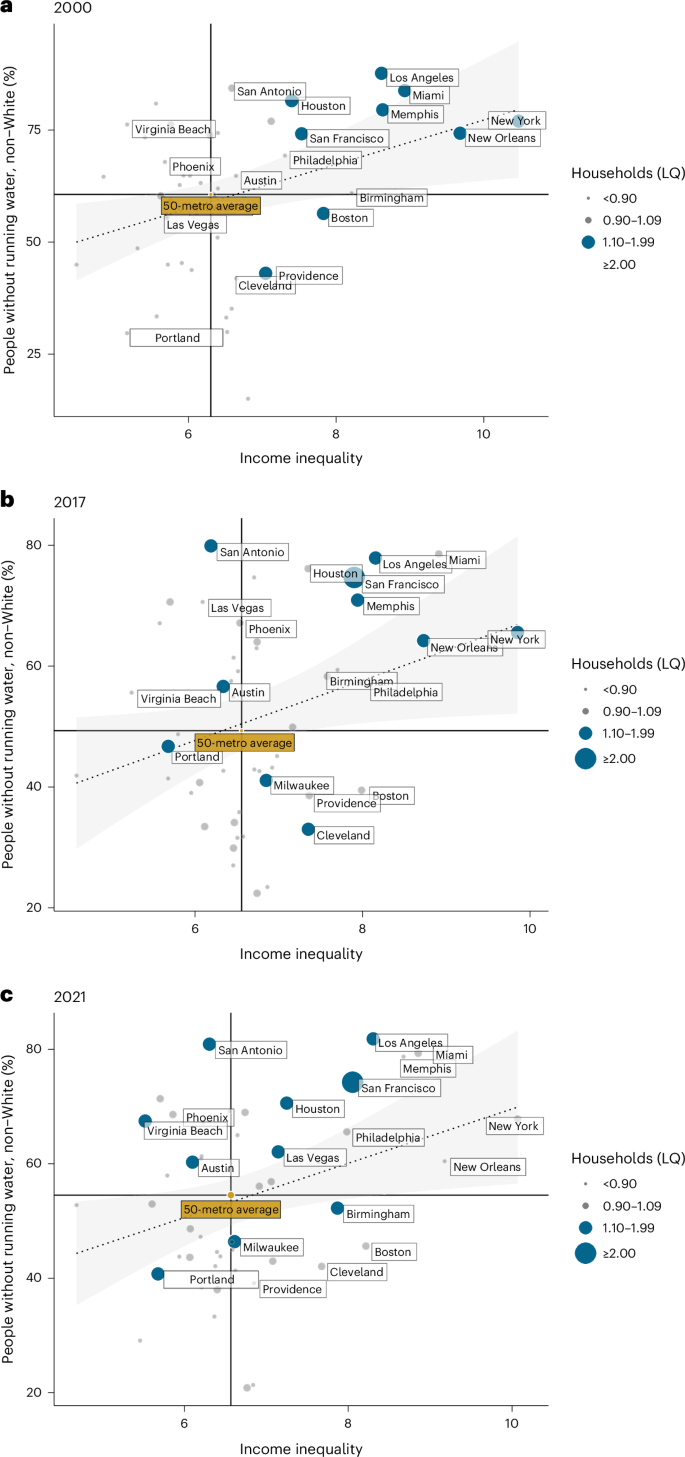

Alarmingly, our evidence shows that the reproductive squeezeâas explored here through its effect on water accessâis expanding to different kinds of US cities, beyond the usual urban suspects. In Fig. 4aâc and Supplementary Video 1, we graphed the movements of the 50 largest US cities from 2000 to 2021 relative to two leading indicators of water insecurity: race and income inequality, both identified as significant predictors of household water access in prior modeling efforts16 (see Methods for details; Fig. 5). The graphs yield three main insights about how the âreproductive squeezeâ is working within and across major US cities: (1) the entrenched racialization of plumbing poverty; (2) a relative stagnation and unimprovement in large US metros and (3) the expansion of the reproductive squeeze in deindustrialized metros.

Graphs display the share of households without running water in individual US cities (the bubbles) relative to race, income inequality and the 50-city average (yellow bubble) from 2000 to 2021. aâc, Graphs present city distributions for 2000 (a), 2013â2017 (b) and 2017â2021 (c). To ensure comparability between cities, we calculated a transformed location quotient (LQ)âa statistic that expresses a ratio valueâto measure each metroâs share of households without running water relative to the 50-metro average. Income inequality refers to the Palma ratio, which measures gross income between top 5% of population to the bottom 20% of the metro population (Methods); for example, each value of 8 indicates that the top 5% population has a gross income 8Ã of the bottom 20%. The dotted line is a visual aid, representing a linear-model trendline of each yearâs x and y values. The shaded area represents the 95th CI of the trendline. This figure visualizes microdata from combined samples and therefore does not report the corresponding margin of error values. Supplementary Video 1 provides dynamic visualization. Source data: US Census Bureau.

Source data

Source data: US Census Bureau.

Source data

The âdanceâ of the bubbles in Fig. 4 illustrates the changing conditions of social reproduction (through household water access) as cities responded to a housing and socioeconomic landscape profoundly transformed by the 2008 financial crisis. In 2000, three major cities are clustered in the upper-right quadrant of Fig. 4a: Los Angeles, New York City and Miami, the âcoastal elitesâ of plumbing poverty, characterized by high levels of income inequality, high shares of non-White households and above-average shares of households without running water. Most cities with above-average levels of plumbing poverty (with the exception of Boston and Providence) are situated in the upper-right quadrant of Fig. 4aâa situation we would expect. In the three other quadrants, the distribution is rather unremarkable: most cities enjoyed greater income equality, less racialized plumbing poverty and below-average shares of households without running water.

By 2017, the configuration changes. Following the global financial crisis, cities with above-average levels of plumbing poverty are no longer exclusive to the upper-right quadrant. In 2017, San Antonio, Austin, New Orleans, Cleveland, Memphis, Portland and Milwaukee emerge with above-average shares of plumbing poverty, scattered across different quadrants (Fig. 4b). San Antonio and Austin (fast-growing Sunbelt cities) sit in the upper-left quadrant of Fig. 4b, exhibiting lower rates of income inequality and high shares of non-White individuals without running water. Milwaukee and Cleveland (classic Rust Belt cities) are located in the lower-right quadrant, demonstrating higher rates of income inequality and lower shares of non-White individuals without running water. All four of these cities scored above-average shares of households without running water.

By 2021, three additional trends are evident that illustrate the changing nature of the reproductive squeeze (Fig. 4c): first, a general vertical shift across all quadrants, indicating the increasingly racialized (non-White) nature of insecure water access in cities; second, the addition of Virginia Beach, Birmingham, Las Vegas and Houston as new hotspots of plumbing poverty; and third, the consistency of Milwaukeeâs position in 2017 and 2021 and the addition of Birmingham in 2021. Together, these results indicate that the reproductive squeeze has expanded reach from typical âcoastal eliteâ citiesâplaces with a longer history of cost-of-living and affordable housing crunchesâtowards new, different urban profiles, such as deindustrialized cities.

Birmingham offers an important example here. A once-thriving industrial center of the American South in the early twentieth century, Birminghamâs fortunes turned negative in the 1950s as it suffered the effects of deindustrialization and toxic race relations during the Civil Rights movement. Today, Birminghamâs main industries include health care, professional and scientific services, finance and insurance. In recent years, Birmingham has promoted urban redevelopment efforts, driven by affordable housing, an increasingly diverse regional economy and an emerging food scene. In short, the dynamic changes presented by Fig. 4 suggest that deindustrialized citiesâsuch as Birminghamâand other places that do not neatly fit the âcoastal eliteâ profile are playing an increasingly prominent role in the evolving story of plumbing poverty.

The relationship of institutionalized racism in shaping water poverty in the United States is well established10,13,16,18,30,31,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Our analysis uniquely illustrates these dynamics over a significant period in the US housing sector, as households of color are increasingly excluded from the âgainsâ of universal water access in US cities. In Fig. 4, the relationship between racialized water access and income inequality (dotted line) is consistent over time, suggesting these variables remain important predictors. However, vertical dispersion in the top two quadrants away from the average line, combined with already high levels of income inequality across the time periods, together suggests that race (non-White) is becoming an increasingly important predictor of urban plumbing poverty. Across US cities, low-income households of color are being left behind from secure water access in ways even more severe than in 2000.

Why? Again, Portland, Oregonâthe whitest large city in the United Statesâoffers a sobering example of the racialized nature of the reproductive squeeze. The number of Portlanders of color without household running water has more than doubled from 1,800 to 4,700 during the past 15 years (Table 1). In 2000, fewer than 250 Black Portlanders lived in homes without running water, just 3.9% of all Portlanders living without access. By 2013â2017, this number had almost quadrupled to >1,100 Black Portlanders (11% of all Portlanders without running water), an increase of 359%. This increase coincided with a period of post-crisis wealth accumulation in greater Portland, in which the growth of various technology industries, real estate development and increased housing values benefitted some Portlanders at the expense of others24. Coupled with Portlandâs post-crisis decline of affordable housing (rental and ownership), weakened protections for renters, stagnant wages and a welfare state with few support mechanisms to alleviate household debt (such as utility bills, student loan repayments and medical debt), we have a scenario in Portland that quietly reinforces and expands systemic disparities at the nexus of housing and water. Without stable housing, there is no secure water access. Such trends do not bode well in terms of meeting the Sustainable Development Goals for sustainable cities (SDG 11) and universal water and sanitation access (SDG 6), in Portland and other US cities facing similar pressures.