No one really knows the cause of migraine, but a number of studies have begun to piece together the mechanisms behind these headaches from hell.

There’s evidence that short strings of amino acids called calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRP) could be the evil puppeteers behind painful migraine attacks, with treatments targeting CGRP already on the market. There are also signs that malfunctioning fluid drainage systems in the brain might sometimes involved.

Now, a research team from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine has found evidence that CGRP could be directly involved in blocking the drainage of cerebrospinal fluid from the brain, creating the pressure and pain experienced during migraine.

“Our study has highlighted the importance of the brain’s lymphatic system in the pathophysiology of migraine pain,” says physiologist Kathleen Caron. “We found that migraine pain is influenced by altered interactions with immune cells and by CGRP preventing cerebrospinal fluid from draining out of the meningeal lymphatic vessels.”

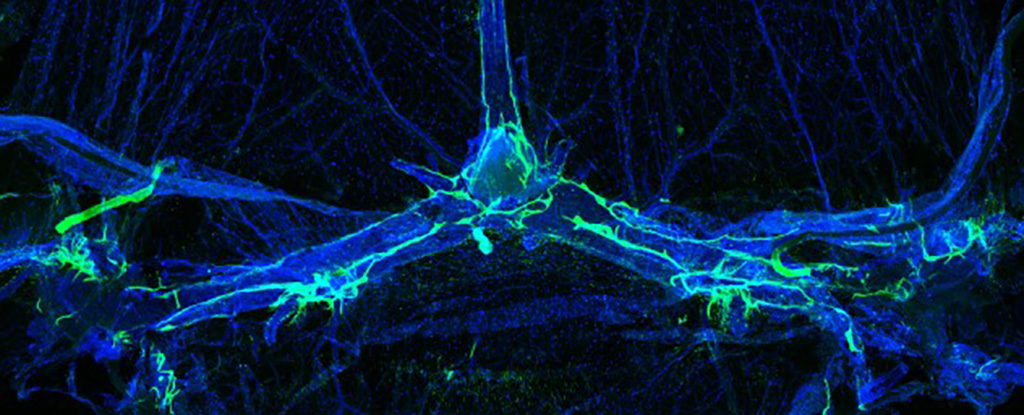

This typically handy neuropeptide is abundant in the layers of brain tissue called the meninges during migraine attacks. Through a series of tests on mice and their cultured cells, the researchers found CGRP not only transmits pain between neurons, it also blocks the flow of fluid from the brain’s lymphatic system, which could account for the feelings of pressure associated with migraine.

In a mouse model of migraine induced by nitroglycerin, mice that were genetically modified to have no lymphatic CGRP receptors – essentially making them ‘immune’ to the neuropeptide – showed significantly reduced chronic migraine pain based on measures using a grimace scale.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is stored within the nervous system in a number of chambers that are connected through a complex plumbing network of meningeal lymphatic vessels. These vessels facilitate the flow of fluids to cerebral tissues in the same way a soaker hose delivers a trickle of water to each plant in a garden row. What’s more, these lymphatic ‘soakers’ also deliver immune cells to the brain’s protective covering, where they can patrol for pests and disease like tiny gardeners.

When the researchers injected CGRP directly into a crucial CSF reservoir in the brains of model-migraine mice, the pores along the MLVs zipped shut, causing the brain’s plumbing to back up and significantly reducing the amount of CSF draining from the skull.

While this new research adds to the growing pile of evidence incriminating CGRP in migraine and especially migraine pain, it’s still unclear exactly what sets off this system-wide breakdown. It does, however, help give a better idea of why anti-migraine therapies that target CGRP are effective, and where in the body they are making that difference.

Next on the agenda is figuring out whether these lymphatic system issues might help explain why there are over three times as many women who experience migraine than men.

“Since lymphatic dysfunction also exhibits a strong prevalence in women, it is tempting to speculate that neurological disorders like migraine could be governed by sex differences in the meningeal lymphatic vasculature,” Caron says.

“If this were true, then new therapeutic strategies or drug targets that enhance meningeal lymphatic and glymphatic flow in women would be desirable.”

This research was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.